Korean Buddhism

Subscribe to this topic via: RSS

Receiving the full range of the Chinese schools since the fourth century, Korean Buddhists created their own synthesis particularly integrating Chan (“Seon 선”) practice with doctrinal study. After suffering centuries of persecution under the Confucian Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), Buddhism today is a weakened but enduring force in Korean culture and thought.

A procession of Buddhist monks carry lanterns decorated with lotuses and Buddhist scenes from their mountain temples to the streets of Seoul for the annual Yeondeunghoe (연등회) lantern festival in celebration of the Buddha's Birthday (석가탄신일). Photo by Daniel Love, 2008.

Table of Contents

Books (8)

Featured:

-

230 pages[recommended but under copyright]

-

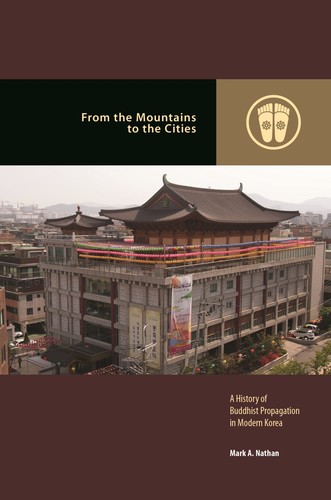

200 pages[recommended but under copyright]

See also:

Readings (24)

Featured:

-

🥇 Best of

This article first examines three interrelated aspects of Korean monastics: (1) the stigmatization imposed on monastics during the Neo-Confucian Joseon dynasty, (2) the persistence of these stigmas in the minds of Koreans, and (3) their internalization among Korean monastics themselves. The article then draws out the impact of these three aspects on the late and limited emergence of lay leadership.

-

⭐ Recommended

From 1982 through 2016, Korean media outlets have reported over 120 instances of vandalism, arson and harassment targeting Buddhist temples and facilities in South Korea. An extension of on-going tensions between South Korea’s Buddhist and Evangelical Protestant communities, this one-sided wave of violence and harassment has caused the destruction of numerous temple buildings and priceless historical artifacts, millions of USD in damages, and one death.

-

The stand-alone practice of memorization of dhāraṇīs appears to have increased in recent years, as evidenced by the mass production of small inexpensive books and series of books for copying and chanting dhāraṇīs and mantras.

-

Venerable P’ŏpt’a 法舵 (b. 1945), AKA ‘the Bodhisattva of Reunification,’ maintains that it is imperative to keep engaging North Korean Buddhists as they are, and to keep providing material help to Northerners—especially food—through Buddhist channels. Doing otherwise would not only be counter to the spirit of universal compassion which typifies Mahāyāna Buddhism, but also leave Southern Buddhists unprepared in the case of unexpected political changes in P’yŏngyang.

-

Paralleling the reinvention of Christmas in the modern period, Buddhists reconfigured the Buddha’s birthday as a symbol of their religious identity and power. The Buddha’s Birthday festival should be understood in the context of increasing contact and exchange among Buddhists in the East and the West. The festival’s prominence was the result of complex negotiation and collaboration between Korean and Japanese Buddhists who both hoped the festival would advance their overlapping visions of Buddhism. The festival was not so much an imposition of the colonizer on a native culture as it was a dynamic, creative feature of modern Korean Buddhism in a colonial context.

-

During the Chosŏn period (1392–1910), the discussion of precepts all but disappeared from the religious discourse in Korean Buddhism. Not only were the precepts left unstudied, but even the performance of official ordination ceremonies for new monks based on the precepts ceased.

-

Therefore, in Wŏnhyo’s One Mind philosophy, enlightenment is the act of returning to the One Mind. This can be achieved through the practice of the six paramitas—generosity, discipline, patience, diligence, meditative concentration, and wisdom—or by chanting to Amitābha with faith in the One Mind and the three Buddhist treasures.

-

Despite its successful Buddhist polemics, Sōtō’s Buddhist teachings in Korea were basically political propaganda viable only within the framework of Japanese colonial imperialism.

-

Kings and ministers thus boasted among themselves over their exclusive fidelity to orthodox Confucian values, even as they worked to assure that the Buddhist institution was aligned with the practical needs of the kingdom.

-

Han wrestled with the task of bridging the gap between institutional Buddhism and lay Buddhism, which had resulted in the deterioration of the Buddhist ideal. In an attempt to find a middle ground that could connect these two extremes, Han’s strategy was to focus on both the Buddhist notion of expediency and the caring spirit of bodhisattva. He was not particularly successful.

-

This article will survey the issues and events surrounding three protests: the 2003 samboilbae, or ‘three-steps-one-bow’, march led by Venerable Sukyong against the Saemangeum Reclamation Project, Venerable Jiyul’s Anti-Mt. Chonsong tunnel hunger-strike campaign between 2002 and 2006, and lastly Venerable Munsu’s self-immolation protesting the Four Rivers Project in 2010.

-

Behind this marriage of the court and Buddhism, however, were the outstanding Buddhist monks who offered the ideology for it.

-

Unaffiliated with any particular school or doctrinal tradition, Wonhyo applied himself to the explication of all the major Mahāyāna source texts that were available at the time, and in doing so had a major impact on East Asian Buddhism.

-

According to the Jogye Order’s 2018 periodic report, the average age of monks is increasing and the number of monks is decreasing. In order to offer solutions to these problems, the report presents and analyzes by dividing those themes into six sub-topics, namely: decrease of births; decrease of postulants; aging of postulants; rapidly changing educational environment; teaching aptitude of educators; education budget.

-

The following discourses were attempts to deal with the problems faced by the Buddhist community during modernization: the discourse on secularity and social participation, the discourse on modernity centering on the issue of modifying precepts, and the discourse on identity contemplating the originality of Korean Buddhism.

-

Scholars have observed that Korean Buddhist nuns have a relatively high social status compared to nuns of other Asian countries, much like their sisters in Taiwan. It is a source of great pride for many Korean bhikṣuṇīs that their community operates with a high degree of autonomy, bringing them to an almost equal standing with their male counterparts. However, this claim of equal status is challenged once the nuns step outside their own communities and into the hierarchical system of the Order, an institution dominated by male monastics.

See also:

Audio/Video (4)

Featured:

-

On how modern, Korean Buddhism has been shaped by the logic of “propagation” in the shadow of Christianity, the West, and authoritarianism.

1h 33 m -

The famous cultural hero, King Sejo (1455–1468), at first he put in place, on the advice of his officials, very punitive and strict regulations around Buddhism. But as time went on, he got sick of the [Confucian State Council] he was dealing with. He started to think that his officials were nuts, I mean actually crazy. You can see in his documents, he himself was being driven crazy having to deal with these people. And the whole issue was Buddhism. They want the recurring thing: to convince a King to go the whole way and kill off Buddhism once and for all.

63 min

See also:

Reference Shelf (1)

-

This liturgical resource provides the texts of traditional Korean Buddhist chants, complete with English translations. It serves the core devotional and ceremonial practices of the Jogye Order, the largest Buddhist order in Korea, emphasizing Seon (Zen) practice and sutras.